Table of Contents

What is amyotrophic lateral sclerosis?

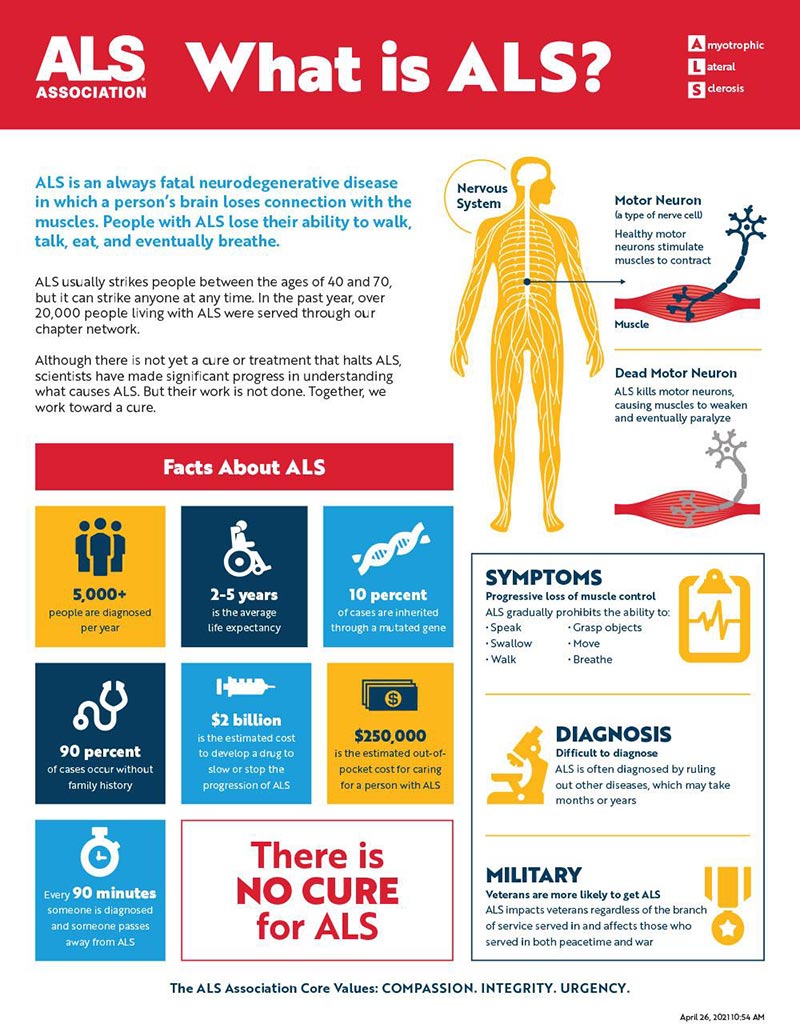

Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig’s Disease, is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects neurons in the brain and the spinal cord. The disease causes nerve cells to degenerate and die, which causes muscles to slowly weaken. This leads to difficulty in speaking, swallowing, and breathing, which ultimately leads to paralysis and death within two to five years of diagnosis.

What are the symptoms?

ALS begins with subtle symptoms, which can be missed. Symptoms often include muscle twitching, cramping, spasticity, muscle weakness in the arm, leg, shoulder, or tongue, slurred and nasal speech, difficulty chewing or swallowing. The first sign of ALS usually appears in the hand or arm and can show as difficulty with simple tasks such as buttoning a shirt, writing, or turning a key in a lock. In other cases, symptoms initially affect one leg. People experience awkwardness when walking or running, or they may trip or stumble more often. When symptoms begin in the arms or legs, it is referred to as “limb onset” ALS; when individuals first notice speech problems it is termed “bulbar onset” ALS.

Early symptoms include:

- Muscle twitches in the arm, leg, shoulder, or tongue

- Muscle cramps

- Tight and stiff muscles (spasticity)

- Muscle weakness affecting an arm, a leg, the neck, or diaphragm

- Slurred and nasal speech

- Difficulty chewing or swallowing

Who gets ALS?

There is no known cure for ALS—so far, it has only be possible to slow its progression by protecting nerve cells from damage with medication and by supporting patients’ quality of life with respiratory equipment, wheelchairs and mobility aides.

The majority of people diagnosed with ALS are over the age of 60 (the risk doubles every 5 years after age 40). Men are 1.5 times more likely than women to be affected by this disease. A small percentage of cases (1-3%) are inherited through a faulty gene. Approximately 10% of cases have no identifiable risk factor; these cases are referred to as “sporadic.”

The primary risk factor for ALS is genetics—about 10% of cases are familial, meaning they are inherited from a parent or sibling. The majority of cases (90%) are sporadic, meaning they occur at random and do not run in families. In both familial and sporadic cases, however, there is a higher risk of developing ALS if you have one or more close relatives with the disease. Other risk factors include smoking cigarettes (as well as exposure to other forms of tobacco smoke) and participating in contact sports like football or boxing (though it’s not yet clear whether concussions have an effect).

What causes ALS?

To date, there is no known single cause of ALS. In most instances, the disease strikes seemingly at random. Though, in some cases, ALS seems to run in families. Scientists have found a number of genes that can cause ALS or make a person more likely to develop the disorder. Some of these genes are related to the function of mitochondria (the energy powerhouses of cells), and others are involved with the immune system’s response to cell damage or stress. Researchers do not yet know how these genes lead to ALS in people who have them.

The most common form of ALS is called “sporadic.” In sporadic ALS, researchers have determined that the chance of inheriting the disease is no higher than it is for the general population. There is also a hereditary form called “familial” which accounts for about 10% of all cases. Individual risk factors associated with familial ALS include male gender, older age at onset and slow progression (which means longer survival).

How is ALS diagnosed?

Tests used to diagnose ALS include:

Electromyography (EMG). In an EMG, a specialist inserts a thin needle electrode through your skin into various muscles. The test evaluates the electrical activity of your muscles when they contract and when they’re at rest. An EMG can reveal abnormal electrical muscle activity that occurs in ALS.

Nerve conduction studies. This test measures how fast nerves conduct electrical signals. Nerve conduction studies can detect nerve damage or dysfunction.

Blood and urine tests. These tests look for abnormalities that may indicate that you have a condition other than ALS that may be causing your signs and symptoms, such as a disorder affecting your thyroid gland (thyroid disease), or a disorder of the muscle known as myasthenia gravis.

Spinal tap (lumbar puncture). Your doctor removes a sample of cerebrospinal fluid — the fluid that surrounds your brain and spinal cord — with a thin needle inserted into the space surrounding your spinal cord (subarachnoid space). The fluid is examined for signs of inflammation or infection, to look for conditions other than ALS that could cause similar symptoms, or to test for abnormal forms of certain proteins associated with genetic forms of ALS.

How is ALS treated?

In most cases, there are no treatments available for ALS. Treatment focuses on relieving symptoms and improving patient quality of life. This can include physical, occupational, speech therapy and respiratory support. For example, a speech therapist might work with patients who have trouble speaking to help them develop alternative methods of communication. A physical therapist might work with patients who have difficulty moving around to help maintain muscle strength by providing special equipment or teaching them exercises they can do at home. The top priorities for treatment are to reduce muscle cramping and spasms, alleviate pain and discomfort caused by muscle spasms or overuse, improve breathing and swallowing, reduce drooling and protect against pneumonia/flu that often occur as a result of these two factors. Patients are also given antibiotics if their illness makes them more susceptible to infections because of their reduced immune response.

What research is being done?

There are also several organizations dedicated to raising awareness and funding research for ALS. These include The Les Turner Foundation, the ALS Association and Project ALS

What is being studied?

There are several active areas of research in the treatment of ALS. Here are a few:

Riluzole. Riluzole is a drug that reduces damage from glutamate, a chemical in your brain and spinal cord that triggers nerve cells to fire. High levels of glutamate have been found in people with ALS, so researchers theorize that too much glutamate may be toxic to nerve cells. Riluzole seems to reduce muscle weakness and prolong survival by slowing the progression of ALS, although it does not reverse muscle weakness or improve quality of life in most people

Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS). In rTMS, an electromagnet is placed near the head to stimulate nerve cells in the brain, triggering them to fire. It has been used as a treatment for depression and migraines, but researchers are trying it now as a treatment for ALS.

Stem Cells. A promising new field of research for ALS is using stem cells to replace motor neurons that have been destroyed by ALS. The ALS Therapy Development Institute has developed a bank of healthy, fully characterized human ALS patient-derived motor neurons that can be used to identify new treatments for the disease. In addition, we have developed a novel treatment platform using patient-specific induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) derived from adult skin cells that can be transformed into virtually any cell type in the body. This cutting-edge technology could enable researchers to generate patient-specific motor neurons and study them while they are alive and before they begin to degenerate.

Drug Discovery. The ALS Therapy Development Institute has developed a drug discovery platform called Project MinE that systematically screens hundreds of thousands of compounds every month in order to identify ALS.

How can I be involved in research?

There are many ways you can be involved in ALS research. With your help, scientists may be able to find the cause of ALS and develop effective treatments.

Participate in a clinical trial

Clinical trials are research studies that involve people. Clinical trials look at new ways to prevent, detect or treat disease. Researchers also use clinical trials to look at other aspects of care, such as improving the quality of life for people with chronic illnesses.

Find a clinical trial near you:

- ALS Association TrialFinder

- CureALS TrialFinder

- Search for clinical trials on ClinicalTrials.gov

- Join a patient registry or biorepository

A registry is a database that collects information about people with a particular disease or condition. Biorepositories store biological samples (such as blood and urine) and medical information from people with a particular disease or condition. Registries and biorepositories help scientists better understand diseases, identify promising areas of research, and learn which treatments work best for different groups of people.

ALS Clinical trials

ALS Clinical trials are a great way to stay up-to-date on the latest research and treatment options for ALS. Each clinical trial focuses on one aspect of the disease and tests a new drug or device, or a new way of administering an existing drug or device. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) has compiled a list of some clinical trials currently in progress. You can search these trials by disease type, site, drug and more. For example, you can search for all “ALS only” clinical trials, which includes clinicaltrials.gov identifiers (NCTs), organized alphabetically from 1 to 50, as well as filtered by phase (“phase 1”, “phase 2”, etc.), drug name and more.